Category: 3.3 Richard Lang Branch

Posts that are mostly about the Richard Lang side of the family, in Washington DC and surrounds

Finding Döbrastocken

I mentioned on the home page, that May of 1982 was a very special time – a magical time in our family’s history. Mom and dad came to visit when we were stationed in Wiesbaden Germany. Of course, they wanted to see us (Dick and Leslie), and they wanted to see their grandchildren (Douglas and Janice). But they had a few other things in mind for that visit. Mom wanted to be reunited with her second cousin, Anton Letang, and dad had several alternate agendas.

Beyond the family visit, his first order of business was to relate to me how he had structured his estate regarding the disposition of his company, Georges’ Screw Machine Products, and its related companies if he and mom passed away. Very typical of dad, it was the ultimate in fairness to all three of his sons.

Next, like many people, he really wanted to find where his father was born. I only knew this because mom told me, not because he asked me directly. So, I asked mom if we had any information about where Grandpa Lang was born. She said, “I think he was born in Oberfranken.” We didn’t know where that was so I went to my German friend Ziggy who owned a restaurant and a whore house. Ziggy said Oberfranken is a whole region of Germany in upper Bavaria. When I queried mom for more detailed information, she said that after World War II, they sent care packages to a place called Döbrastocken. Of course, nobody knew where that was either.

Now it was a quest. How to make it happen for dad, this man that gave me everything and asked nothing in return. Luckily, I was a Deputy Commander of a large Air Force reconnaissance unit. If we couldn’t find a place on map, who could? So, I called one of my airmen in a building across the compound from my office and asked if we had a World Gazetteer. After getting a yes, I asked him to look up a place called Döbrastocken, umlaut and all. He called back about an hour later and provided latitude and longitude coordinates in degrees, minutes, seconds.

Well what do you want? This is the Air Force! We’re not the Army with UTM coordinates of a mortar target just over the ridge line. We bomb things from aircraft! So, when I asked him to bring me a map, he brought a Jet Navigation chart. Next task, roll out on our picnic table the 5 ft. x 3 ft. chart covering most of Europe, and use a straight edge to plot an X on the map. There’s no detail there of course.

So, the family decided on an adventure. We set out heading east toward the Czech border in two cars: Leslie, mom, and Janice in our late model Opel, and me with dad and Douglas in an older Mercedes. After one overnight where we bought some wonderful crystal, we were off the Autobahn on country roads. A road sign appeared, pointing the way to the village of Döbra. So, if there’s a Döbra, there could be a Döbrastocken. We pulled into Döbra about mid-morning on a Saturday. Not sure what German women do now on Saturday mornings, but at least in the 1980s some came out to sweep the gutter of the street. I got out of the car and, although very far from fluent in German, I was confident of pulling off that conversation. “Excuse me, can you please tell me where I can find Döbrastocken.” She looked up and asked what my family name was. Totally baffled! My German just isn’t that bad. So, I asked again. And she asked again. When I said “Lang. Ich bin Herr Lang.” She replied, “Jah Herr Lang” and proceeded to tell me how to find Döbrastocken which was just outside the village. You probably still can’t find Döbrastocken by typing it into Google Maps, but you’ll get very close by looking up “Döbra, Schwarzenbach am Wald”. You’ll find that it’s about a 30 minute drive from the larger town of Hof, which is very close to the Czech border.

It turns out that Döbrastocken is just three farmhouses down a road outside the village of Döbra. We stopped at the first and asked young boys if they knew of the Langs. They didn’t. Next, we drove to an old house that was all boarded up. Could that be it? I went to the third house and knocked on the door. Not polite I know, but I thought the man who came to the door was probably older than the dirt. He was very hard of hearing so I called for the other quasi-German speakers (mom and Leslie) to join me. The man confirmed that the Langs had lived in that boarded up house but no one lived there anymore (which was obvious). At mom’s suggestion, we got back in the cars and returned to Döbra, knowing that there was probably a cemetery associated with the village church. We were right, and there’s nothing like six Americans walking around your cemetery and into your church to draw the attention of the pastor. We had a nice chat with him during which we learned that the last Lang to have lived in that house was a woman who had married 16 years earlier and moved away with her husband.

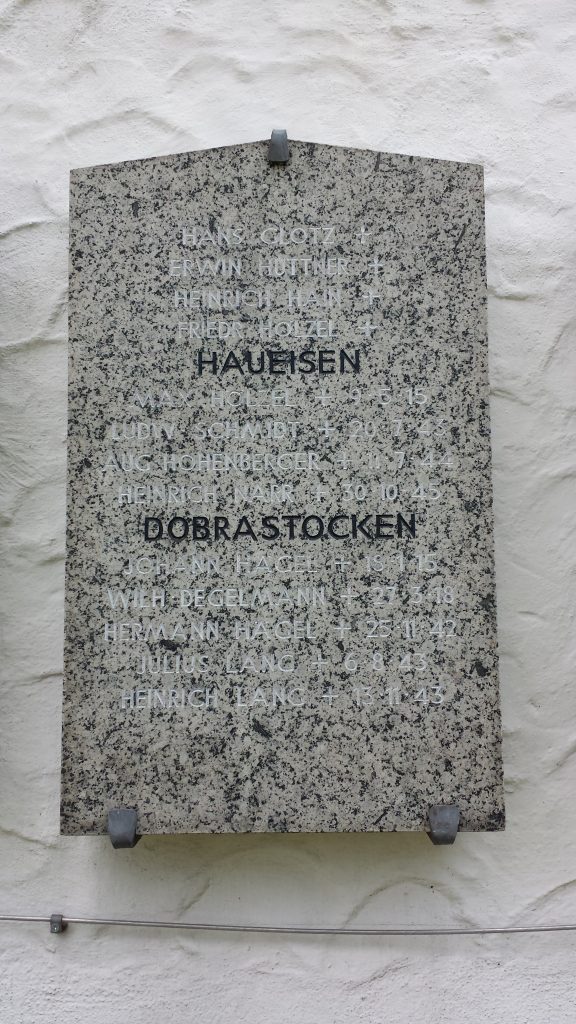

It’s a good thing Mom took pictures of those Lang gravestones because they’re no longer there. Leslie and I went to Döbra in July 2019 and learned that gravestones are removed after 25 years. The timing probably also depends on whether or not someone is paying for the upkeep of the gravesite. But new Lang gravestones are there and members of a small band told us to look at a war memorial on the side of the church. Sadly, two Lang names from Döbrastocken are there, having been killed in WWII in 1943. There’s also a Lang bakery in Döbra. The woman who waited on us said that a Frau Lang lived upstairs but she didn’t seem inclined to go find her.

It was quite a successful adventure, but the magical part was the inspiration to start recording our history for future generations.

The Donauschwaben

Wait! I thought we were German. So why talk about Serbia? And what does Yugoslavia have to do with my maternal grandparents Franz Kahles and Anna Quint? To answer these questions, let’s start with a little Wikipedia history lesson.

The Danube Swabians (in German – Donauschwaben – (doe’-now-schwaben)) is a collective term for the German-speaking population who lived in various countries of southeastern Europe, especially in the Danube River valley. Most were descended from 18th-century immigrants recruited as colonists to repopulate the area after the expulsion of the Ottoman Empire.

Because of different historic developments within the territories settled, the Danube Swabians cannot be seen as a unified people. They include ethnic Germans from many former and present-day countries: Germans of Hungary; Satu Mare Swabians; the Banat Swabians; and the Vojvodina Germans in Serbia’s Vojvodina, who called themselves “Schwowe”in a Germanized spelling or “Shwoveh” in an English spelling; and Croatia‘s Slavonia. In the singular first person, they identified as a “Schwob” or a “Schwobe”. Wherever I heard my mother, Marian Lang, speak German I would tell her that she spoke German like a Schwob. She would reply: “That’s because I am a Schwob.”

Origins

Beginning in the 12th century, German merchants and miners began to settle in the Kingdom of Hungary at the invitation of the Hungarian monarchy. Although there were significant colonies of Carpathian Germans in the Spiš mountains and Transylvanian Saxons in Transylvania, German settlement throughout the rest of the kingdom had not been extensive until this time.

During the 17th-18th centuries, warfare between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire devastated and depopulated much of the lands of the Danube valley, referred to geographically as the Pannonian plain. The Habsburgs ruling Austria and Hungary at the time resettled the land with people of various ethnicities recruited from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including Magyars (Hungarians), Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Serbs, Romanians, Ukrainians, and Germanic settlers from Swabia, Hesse, Palatinate, Baden, Franconia, Bavaria, Austria, and Alsace-Lorraine. Despite differing origins, the new immigrants were all referred to as Swabians by their neighbor Serbs, Hungarians, and Romanians. The Bačka settlers called themselves Schwoweh the plural of Schwobe in the polyglot language that evolved there. The majority of them boarded boats in Ulm, Swabia, and traveled to their new destinations down the Danube River in boats called Ulmer Schachteln. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had given them funds to build their boats for transport.

Settlement

The first wave of resettlement came after the Ottoman Turks were gradually being forced back after their defeat at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. The settlement was encouraged by nobility, whose lands had been devastated through warfare, and by military officers including Prince Eugene of Savoy and Claudius Mercy. Many Germans settled in the Bakony (Bakonywald) and Vértes (Schildgebirge) mountains north and west of Lake Balaton (Plattensee), as well as around the town Buda (Ofen), now part of Budapest. The area of heaviest German colonization during this period was in the Swabian Turkey (Schwäbische Türkei), a triangular region between the Danube River, Lake Balaton, and the Drava (Drau) River.

After the Habsburgs annexed the Banat area of Central Europe from the Ottomans in the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718), the government made plans to resettle the region to restore farming. It became known as the Banat of Temesvár (Temeschwar/Temeschburg), as well as the Bačka (Batschka) region between the Danube and Tisza (Theiss) rivers. Fledgling settlements were destroyed during another Austrian-Turkish war (1737–1739), but extensive colonization continued after the suspension of hostilities.

The late 18th-century resettlement was accomplished through private and state initiatives. After Maria Theresa of Austria assumed the throne as Queen of Hungary in 1740, she encouraged vigorous colonization on crown lands, especially between Timișoara and the Tisza. The Crown agreed to permit the Germans to retain their language and religion (generally Roman Catholic). The German farmers steadily redeveloped the land: drained marshes near the Danube and the Tisza, rebuilt farms, and constructed roads and canals. Many Danube Swabians served on Austria’s Military Frontier against the Ottomans. Between 1740 and 1790, more than 100,000 Germans immigrated to the Kingdom of Hungary.

The Napoleonic Wars ended the large-scale movement of Germans to the Hungarian lands, although the colonial population increased steadily and was self-sustaining through reproduction. Small daughter-colonies developed in Slavonia and Bosnia. After the creation of Austria-Hungary in 1867, Hungary established a policy of Magyarization whereby minorities, including the Danube Swabians, were induced by political and economic means to adopt the Magyar (Hungarian) language and culture.

With the treaties ending World War I, the Banat was divided between Romania, Yugoslavia, and Hungary; Bačka was divided between Yugoslavia and Hungary; and Satu Mare went to Romania. In Yugoslavia, the death of Tito (1980) gravely weakened communist rule, and the waves of liberation washing over other parts of the communist world in the late 80’s and early 90’s led to the dissolution of the country. Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia and Montenegro, and Macedonia, all became separate states.

I will update this post with maps that provide a time-phased view of the changing boundaries and kingdom/country names over the centuries and show the country or empire our family of Danube Swabians belonged to during these different times.

Culture

The Danube Swabian culture is a melting pot of southern German regional customs, with a large degree of Balkan and mostly Hungarian influence. This is especially true of the food, where paprika is heavily employed, which led to the German nickname for Danube Swabians as “Paprikadeutsche”. The architecture is neither Southern German nor Balkan but is unique to itself.

Language

The Danube Swabian language is only nominally Swabian (Schwowisch in the Bačka). In reality, it contains elements or many dialects of the original German settlers, mainly Swabian, Franconian, Bavarian, Rhinelandic/Pfälzisch, Alsatian, and Alemannic, as well as Austro-Hungarian administrative and military jargon. Loanwords from Hungarian, Serbian, or Romanianare are especially common regionally regarding cuisine and agriculture, but also regarding dress, politics, place names, and sports.

Many German words used by speakers of Danube Swabian dialects may sound archaic. To the ear of a Standard German speaker, the Danube Swabian dialect sounds like what it is: a mix of southwestern German dialects from the 18th century.

Popular names for women include: Anna, Barbara, Christina, Katharina, Magdalena, Maria, Sophia, Theresia, and many two-name combinations thereof. Popular names for men include: Adam, Anton, Christian, Friedrich, Georg, Gottfried, Heinrich, Jakob, Johann, Konrad, Ludwig, Mathias, Nikolaus, Peter, Philipp (or Filipp), and Stefan (or Stephan). With so few names in villages, other modifiers or nicknames were almost always used to distinguish people.

We’ll rejoin this region later in the family story when we learn about mom’s second cousin, Anton Letang, and what happened leading up to and during World War II.

Mom and Sailors

Some background. My dad, George E. Lang Sr., was prime draft age as the United States entered World War II. When he received his draft notice, his employer went to the authorities and told them (truthfully) that his company had contracts to make critical components for the U.S. Navy and without George Lang he wouldn’t be able to fulfill them. As a result, the Draft Board gave dad a deferment.

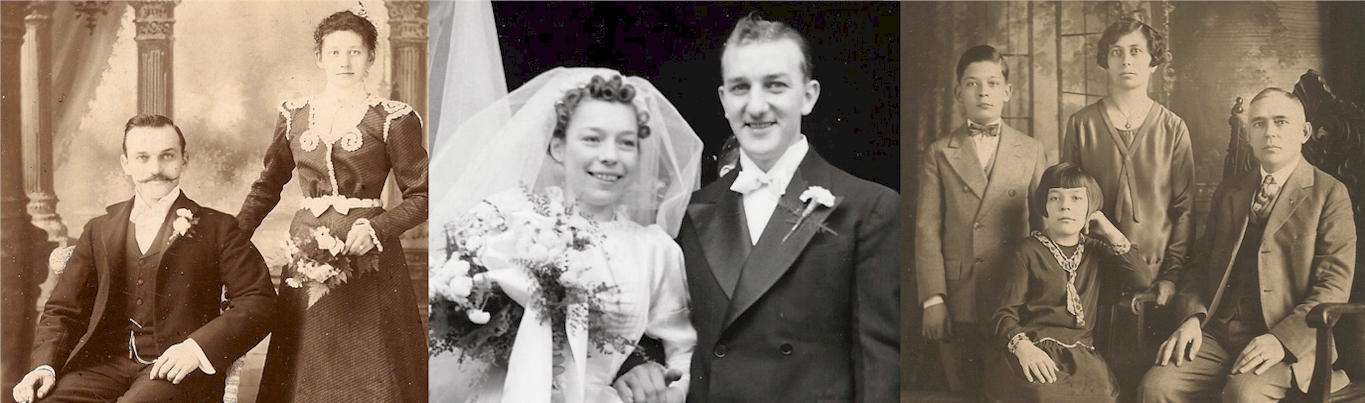

That deferment lasted through my brother George’s birth in June of 1942, my birth in October of 1943, all of 1944, and on through late spring of 1945. At that point, he received notice to report for induction into the military. Since he would be going overseas in the Army, my mom wanted a photo of herself and the two boys for him take along. Her father, my grandfather Frank Kahles, took her to a studio and had this photo made.

This time, both his company and fate intervened. Just after dad notified his employer of his draft notice, he received a call from a company officer who was in Washington, DC on business. That officer told him emphatically to ignore the notice and not to report. My parents were in a pickle. The company said don’t report, but he could get arrested. What to do??? Two days later, the war was over. Guess that guy knew something but couldn’t say it out loud.

Recent Comments